An experienced arts educator and columnist who lived in Tokyo and London from 1980 to the 90s. Especially interested in creative industries.

After teaching fine art courses for over 20 years, I have emphatically answered endless questions about the value of art. As art is created from the heart, it can be totally groundless or can just be an impulsive pursuit of aesthetic consciousness. If the value of an artwork is to be judged, it is simply not something solely determined by the artist. Undoubtedly, the most important function of art is to inspire the mind through aesthetic experience and perception, just like when a random sight of a beautiful house would lead us to slow down our pace and fantasise about the joys of living inside. When it comes to how much you’re willing to pay for that inspired feeling, I am not totally sure where to start.

Here is my take: suppose there are one canvas and one towel. Both feature an identical image. The canvas is hand-painted in oil or watercolour while the towel is machine-printed, and dozens of such towels can be produced every minute. Even if there’s Mona Lisa on the towel with her kisses figuratively drying you off after you take a shower, it doesn’t take expert analytical skills to figure out the towel is worth less than the painting. However, the very same towel in terms of size and material, would appeal to different customers in different marketplaces if they feature different images or patterns—this is how other elements like culture and traditions come into play.

The so-called phenomenon of creative products that demonstrate local culture and traditions, simply called “cultural and creative products” by economic theorists, first emerged in Britain before becoming prevalent around the world. As time went on, perhaps it has become apparent that the only thing that is fashionable about the cultural and creative industry is the use of the term “cultural and creative products”. To be frank, what products that are neither culturally relevant nor particularly creative can remain on the market? Take a look at the shops around us and observe the things that tourists are willing to fork over cash for. While not necessarily essential for daily living, these items at least serve certain functions, be it a little trinket created out of serendipity by a fine arts master degree student. A customer can take a look at it and put it back gently with a smile after asking the price just for kicks. However, if you have the patience, a connoisseur for your art would show up right before the very same item, seemingly out of nowhere from the leisurely Sunday market crowd, offering to buy it at your price without any hesitation and then tell you in a jubilant mood that you have to keep doing what you’re doing.

London’s Portobello Road Market was once the world’s most famous spot for treasure hunting. Lined with a variety of shops and market stalls that stretches more than 1km, the market features an impressive array of products from vintage antiques to trendy gifts. Every Saturday from the early morning around 5–6am, it’s easy to spot many slightly hung-over vendors, young and old, tending their wares lying in front of you, waiting to be purchased with a sense of hope.

If you like, you can really take your time having fun at every stall, haggling and slowly making up your mind. Then you put the items gently back on the table with a grin, turn around, leaving the person next to you repeating what you have just done while it’s unclear whether he or she would appreciate the wares from the vendor. In recent years, authentic antiques are getting harder and harder to come by, same for vintage items from classic brands. What is left are the presentable second-hand goods and the trendy, so-called cultural and creative products.

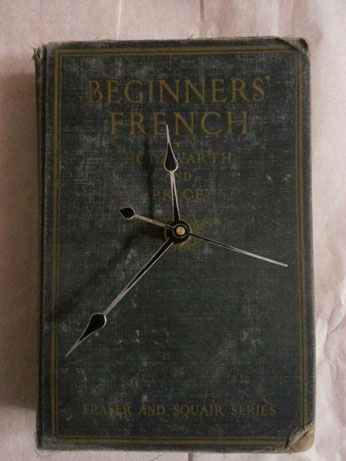

It goes without saying that the biggest difference between products coming from design institutes and the handmade arts and crafts lies in the cost; the former’s production orientates towards quantity while the latter is created with bliss and joy by following the heart—like turning a very thick book into a book clock by placing a clock inside the hollowed part in the middle. With a set of sturdy clock hands on the cover, the item adds a quirky sense of fun to a desk. It costs around 7–8 pounds each, and I would catch up with the young craftsman every time I pass by. When I see one that takes my fancy, I’ll buy it for friends who have never read a book.